Loading content - please wait...

Polydorella spionid worms whip their food

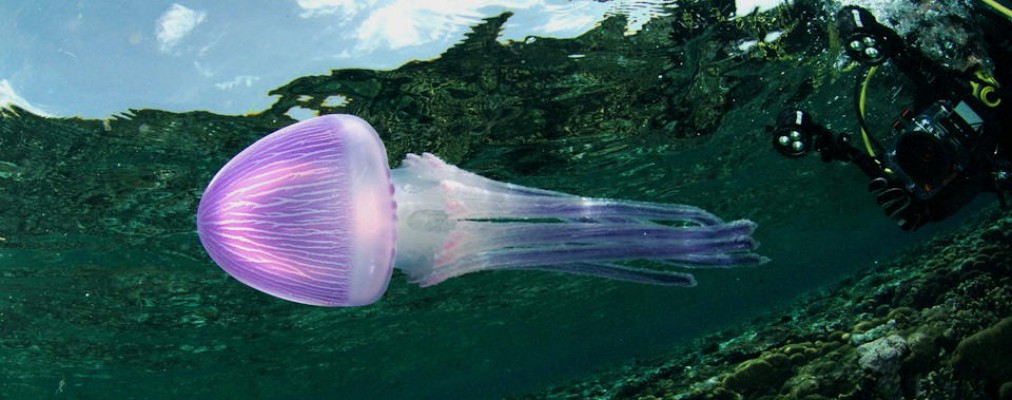

Polydorella spionid worms crowded the upper surface of a sponge. Their feeding activity caught the attention of a Miguel’s Diving staff. Since they are super tiny, the sponge seemed to be covered by wiggling hairs.

A Mystery Solved

With such rich marine life, the reefs of Gorontalo are truly a hidden paradise. Despite operating since 2003, our staff had never noticed Polydorella spionid worms. They typically live on the surface of sponges of which Gorontalo has many. However, these segmented worms only reach 1.5 millimeters in length. Their typical width is only 0.4 millimeters. No wonder they are easily overlooked.

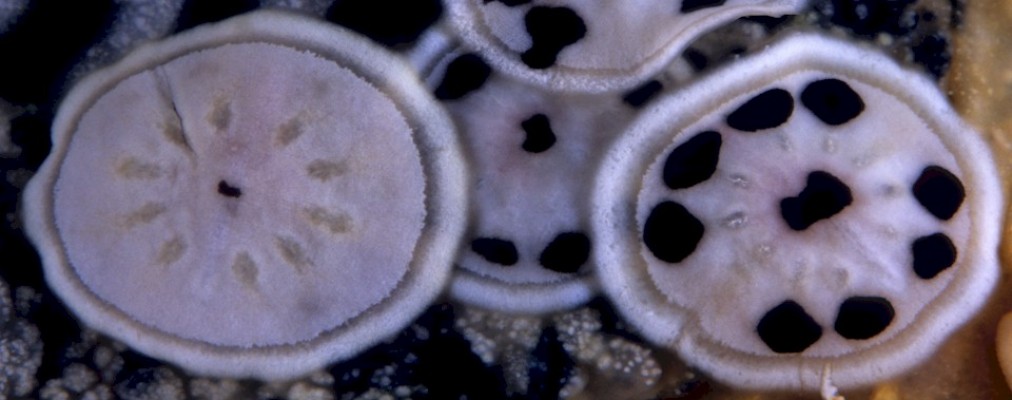

However, on a dive at Sand Channels dive site, the surface of one sponge seemed to be quivering with dark hairs. According to the dive master who saw this activity, sponges of that type never displayed such frenetic motion. With the help of an excellent underwater photographer, a documentary photograph helped identify the tiny creatures that caused the pulsating appearance of the sponge’s surface. Upon seeing the photograph, Dr. Leslie Harris of Los Angeles County Natural History Museum confirmed those tiny worms were a species of Polydorella. That is one genus of spionid worms. The whips are their feeding palps. So, the motion that caught our attention was a great gathering of feasting Polydorella spionid worms.

Reproduction in Polydorella spionid worms

All members of the Polydorella genus undergoes asexual reproduction. The process is called paratomy. This type of worm has about fifteen segments, depending on the species. Basically, the worm grows additional segments. Upon reaching a certain length, a middle segment will develop into a head. Eventually, the new segments will separate from the parent segments. Scientists call the parental worm a stock and the new worm a stolon. Genetically, they are identical. The growth area on the parental stock follows segment ten or eleven. Moreover, a chain of up to five individuals can form prior to separation.

Sexual reproduction is rare among Polydorella spionid worms. Only P. kamakamai and P. smurovi are documented as producing eggs. Indeed, eggs are rare. In research, only one of 290 Kamakama worms had eggs. That amounts to less than half of a percent. No eggs were found in the worms’ burrows. However, the Polydorella spionid worms photographed in Gorontalo contained multiple individuals bearing eggs. The egg sacs appear as white ovals in the picture. So, the documentation of so many eggs sacs makes this an extraordinary photo.

Life on a Sponge

These tiny worms live on various sponges. Sometimes, their mud tunnels can be observed on the surface of a sponge. Researches of Polydorella spionid worms in the Red Sea found sand grains in the intestines of the worms. For such a tiny creature, a sand grain is large to swallow. Scientists do not know why these worms would swallow sand grains, since they have no nutritional value. However, speculation is that worms help keep a sponge surface clean. In that way, the sponge enjoys benefit from hosting such tiny creatures.

In the photograph

, the double whips coming from the worm’s head are used to gather food from the water or surface of the sponge. The motion of mass feeding caught the eye of our dive master in February 2019 when the photograph was taken.Additionally, a couple of years later in June 2021, another of our dive masters photographed a Striped triplefin (Helcogramma striatum) eating Polydorella spionid worms. They were on an orange sponge.

These two photographs show how skilled Miguel’s Diving staff are in finding unusual critters in the ocean. For your chance to dive with our excellent dive masters, please make your dive reservations directly with Miguel’s Diving.