Loading content - please wait...

Kayak.com features Miguel’s Diving

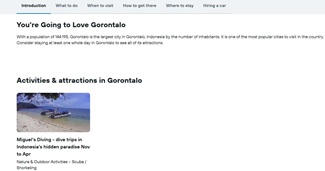

Kayak.com is a strategic player in the online travel market, processing billions of searches annually. Now, it’s information page on Gorontalo activities features Miguel’s Diving.

Gorontalo Travel Guide on Kayak.com

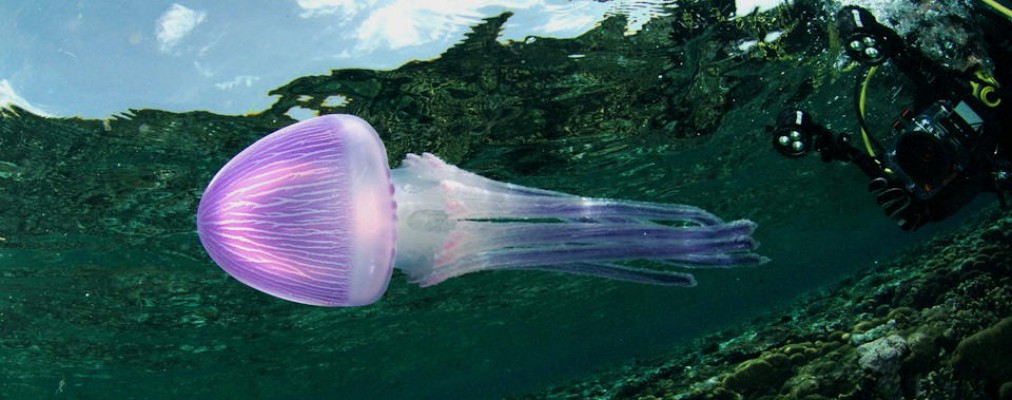

The booking platform Kayak.com is adding destination travel guides for its locations. Recently, they contacted Miguel’s Diving, asking for a photo and basic information helpful for dive travelers. We were happy to accommodate their request.

On their travel guide for Gorontalo, they provide information like population, weather, and hotel options. Now, that guide includes a photo of our dive boats moored along a deserted beach not far from our dive center.

The Kayak travel group began in 2004 with only fourteen staff. Now there are over one thousand, operating seven international brands. Searches for flights, ground transportation, and travel packages are currently available in more than twenty languages. Additionally, in 2013 they acquired Booking Holding, a major travel player in online travel.

Flights to Gorontalo

We have added a link to Kayak.com to the Flights & Travel page on our website. Oftentimes, Indonesian domestic airlines do not accept foreign credit cards for flight bookings. Fortunately, the Kayak website will.

The ease of payment with credit card is only one advantage for flight bookings. For mysterious reasons, domestic carriers in Indonesia supply only limited options on their own websites. One example is the Lion Air website. Travelers wishing to fly from Denpasar, Bali (DPS) to Gorontalo (GTO) are not given complete options. The best flights are via Makassar (UPG). However, flights with that transit option do not appear on the Lion Air website! They are available with Kayak.com.

Gorontalo’s Airport

Our modern airport is located in the central valley of Gorontalo. Because this valley is ringed with mountains, the air approach usually circles over our dive center, above Gorontalo City, and onwards to Limboto Lake. The drive from the airport takes less than one hour.

For flights to Gorontalo, Kayak.com is a great option. For diving, make your dive reservations directly with Miguel’s Diving.